Coree Coppinger: Fight Club Photographer

My tenure as web committee chair for the Coalition of Photographic Arts introduced me to a lot of first-rate photographers. In this 2009 Q&A, I spoke with Coree Coppinger about her documentary work with the Duke Roufus Mixed Martial Arts Academy.

First of all, Coree, how did this project come about?

The project started in February of 2009. I was recovering from a broken foot. It was frigid, sub-zero weather and I desperately needed some project to shoot that did not demand my being outdoors. I let my fingers do the walking in the Yellow Pages and I kept coming back to these martial arts places. I thought maybe I could get a few good action shots. So I called all of them and waited for a reply and the first place to reply was the Duke Roufus club. I had no idea I would become so involved with the personalities there. I was not allowed to shoot with a flash, so I was faced with whatever lighting was available. I discovered that shooting action without a flash in uncontrolled lighting was indeed a challenge.

What did you do to compensate for those lighting limitations?

I would change back and forth from manual to speed priority. I discovered a couple of spots that I deemed were magic light spots. I figured the best setting for those spots both in manual and in speed priority. I then would shoot anyone who ventured under those lights. The rest was a hit or miss situation, meaning the light may be good for an angle but if moved by a hair the lighting would change drastically. So with every shot I took I had to adjust for that angle and spot. I push the shadows so I usually underexpose my shots. This helps me keep the hard lights by pitting the fluorescent spots against the shadows. I know my meter settings so with a glance at my harsh marks on my meter I can tell if I am in the ball park of where I need to be. I use high contrast to help keep a gritty flavor for most.

What challenges did you face in gaining the trust of the fighters you were shooting?

Now that is a hard one. They did not trust a camera, and they did not trust an older female behind the camera. I just showed up time and time again. Finally one or two would ask questions like why are you taking our pictures? I just replied for a gallery show. As they became more used to a camera lens being stuck in their faces, they started joking around, a little more, I being the butt of their jokes. I soon started making remarks about their remarks, and some of the tension eased. I picked a few guys out who were photogenic and I seemed to be able to talk with more easily, like Chuck and his friend Andric. Chuck, once a skinhead, tattooed from neck to foot, a very nice guy. Unlikely pairing skinhead and black American but they worked well together. One of the things I never do is judge. The type of shooting I do a lot of demands an open mind, so passing judgment on another being, pushing my morals off on someone else would get me nowhere. So I try to learn a lot about different subjects to ensure I can engage in some type of dialog with most people. Being able to relate to their place in life, makes or breaks that reach for trust.

The project started in February of 2009. I was recovering from a broken foot. It was frigid, sub-zero weather and I desperately needed some project to shoot that did not demand my being outdoors. I let my fingers do the walking in the Yellow Pages and I kept coming back to these martial arts places. I thought maybe I could get a few good action shots. So I called all of them and waited for a reply and the first place to reply was the Duke Roufus club. I had no idea I would become so involved with the personalities there. I was not allowed to shoot with a flash, so I was faced with whatever lighting was available. I discovered that shooting action without a flash in uncontrolled lighting was indeed a challenge.

What did you do to compensate for those lighting limitations?

I would change back and forth from manual to speed priority. I discovered a couple of spots that I deemed were magic light spots. I figured the best setting for those spots both in manual and in speed priority. I then would shoot anyone who ventured under those lights. The rest was a hit or miss situation, meaning the light may be good for an angle but if moved by a hair the lighting would change drastically. So with every shot I took I had to adjust for that angle and spot. I push the shadows so I usually underexpose my shots. This helps me keep the hard lights by pitting the fluorescent spots against the shadows. I know my meter settings so with a glance at my harsh marks on my meter I can tell if I am in the ball park of where I need to be. I use high contrast to help keep a gritty flavor for most.

What challenges did you face in gaining the trust of the fighters you were shooting?

Now that is a hard one. They did not trust a camera, and they did not trust an older female behind the camera. I just showed up time and time again. Finally one or two would ask questions like why are you taking our pictures? I just replied for a gallery show. As they became more used to a camera lens being stuck in their faces, they started joking around, a little more, I being the butt of their jokes. I soon started making remarks about their remarks, and some of the tension eased. I picked a few guys out who were photogenic and I seemed to be able to talk with more easily, like Chuck and his friend Andric. Chuck, once a skinhead, tattooed from neck to foot, a very nice guy. Unlikely pairing skinhead and black American but they worked well together. One of the things I never do is judge. The type of shooting I do a lot of demands an open mind, so passing judgment on another being, pushing my morals off on someone else would get me nowhere. So I try to learn a lot about different subjects to ensure I can engage in some type of dialog with most people. Being able to relate to their place in life, makes or breaks that reach for trust.

Once you had your images, how did go about choosing the images you wanted to exhibit ?

At this very moment I am still choosing. I look for composition, but also for something that speaks to me. It does not have to be perfect but it has to talk. The tilt of the head, the mouth, the eye, something which reflects the fighter’s state of being. That is why I only take candid pictures. I am really trying to catch the soul at the time.

I like the candid approach too. Seems more "real" than a posed shot (though some may argue that point!). Now that you've spent time with the fighters, on the computer editing the shots, and finally getting feedback from people viewing your photos, what are the lessons you've taken away from doing this project?

Posed is for show, creating an image, a look desired. Candid is raw, a moment in that person’s life which reflects a thought, emotion, and stress of that person. One is contrived in some way and the other real. The challenge for me is bringing "real" into a fine art situation.

Much of that depends on lighting and composition. Fighters want to look tough, journalists want flat action, I want impact. My work does not convey violence, I let the subjectiveness of black and white and the gritty quality of my pictures convey that. Many people don't like graininess, but to me it is the subtle interjection of texture which remains imbedded into the unconscious.

Getting good clean sharp shots and trying to maintain the right amount of grittiness can't be seen in the camera. Once you see it in post well then you start kicking yourself. Bringing down your ISO in low light can make the shot soft; bring up the ISO and you get noise/grain but a sharper image. I don't want always to have stop action so finding the spot which is pleasing to the eye yet not frozen. I have not mastered it yet.

The hardest is choosing the right shots for the show. That is one thing I go over and over again and never seem to learn. My lack of experience with light is troublesome to me. You need to know light to capture the right moods. I get statements about how much someone likes something or dislikes it and this is important to me but it is what they remember and carry emotionally about the body of work which really tells me if I have failed or not.

Negative and positive are two sides of a coin, it is the impact down the road that makes my shot a success. You see, if they don't like a shot, but it stays with them, and they reflect on it in some way, then I have done my job. I have a lot to learn about shooting action with available light, and a whole lot more in composition to experiment with. I learn from mistakes and from my peers. They bring a new set of eyes and help me analyze a picture from a different perspective. My biggest lesson from my body of work is how much I don't know and how much more work I have ahead of me. I will keep plugging away at it.

At this very moment I am still choosing. I look for composition, but also for something that speaks to me. It does not have to be perfect but it has to talk. The tilt of the head, the mouth, the eye, something which reflects the fighter’s state of being. That is why I only take candid pictures. I am really trying to catch the soul at the time.

I like the candid approach too. Seems more "real" than a posed shot (though some may argue that point!). Now that you've spent time with the fighters, on the computer editing the shots, and finally getting feedback from people viewing your photos, what are the lessons you've taken away from doing this project?

Posed is for show, creating an image, a look desired. Candid is raw, a moment in that person’s life which reflects a thought, emotion, and stress of that person. One is contrived in some way and the other real. The challenge for me is bringing "real" into a fine art situation.

Much of that depends on lighting and composition. Fighters want to look tough, journalists want flat action, I want impact. My work does not convey violence, I let the subjectiveness of black and white and the gritty quality of my pictures convey that. Many people don't like graininess, but to me it is the subtle interjection of texture which remains imbedded into the unconscious.

Getting good clean sharp shots and trying to maintain the right amount of grittiness can't be seen in the camera. Once you see it in post well then you start kicking yourself. Bringing down your ISO in low light can make the shot soft; bring up the ISO and you get noise/grain but a sharper image. I don't want always to have stop action so finding the spot which is pleasing to the eye yet not frozen. I have not mastered it yet.

The hardest is choosing the right shots for the show. That is one thing I go over and over again and never seem to learn. My lack of experience with light is troublesome to me. You need to know light to capture the right moods. I get statements about how much someone likes something or dislikes it and this is important to me but it is what they remember and carry emotionally about the body of work which really tells me if I have failed or not.

Negative and positive are two sides of a coin, it is the impact down the road that makes my shot a success. You see, if they don't like a shot, but it stays with them, and they reflect on it in some way, then I have done my job. I have a lot to learn about shooting action with available light, and a whole lot more in composition to experiment with. I learn from mistakes and from my peers. They bring a new set of eyes and help me analyze a picture from a different perspective. My biggest lesson from my body of work is how much I don't know and how much more work I have ahead of me. I will keep plugging away at it.

Mike Starling's original music is heard on numerous recordings and soundtracks, and his stories and photos have been featured in books, films, mags and other media.

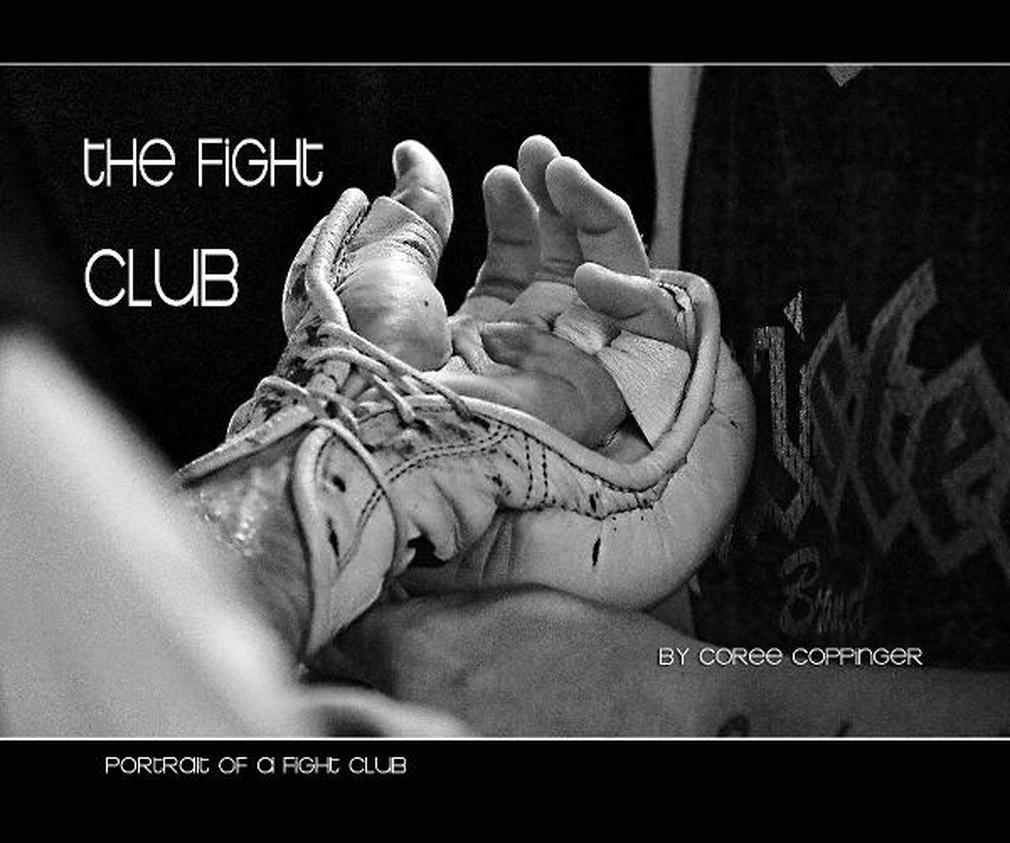

starlingarchive.weebly.com is the authorized website for samples of published work by the Wisconsin-based writer, artist and musician Mike Starling. Photo of Starling on assignment in Ireland by J. Winke. Fight Club photo and book cover by Coree Coppinger. Website developed and managed by Nine Volt Media. ©MMXX-MMXXIII. All rights reserved.